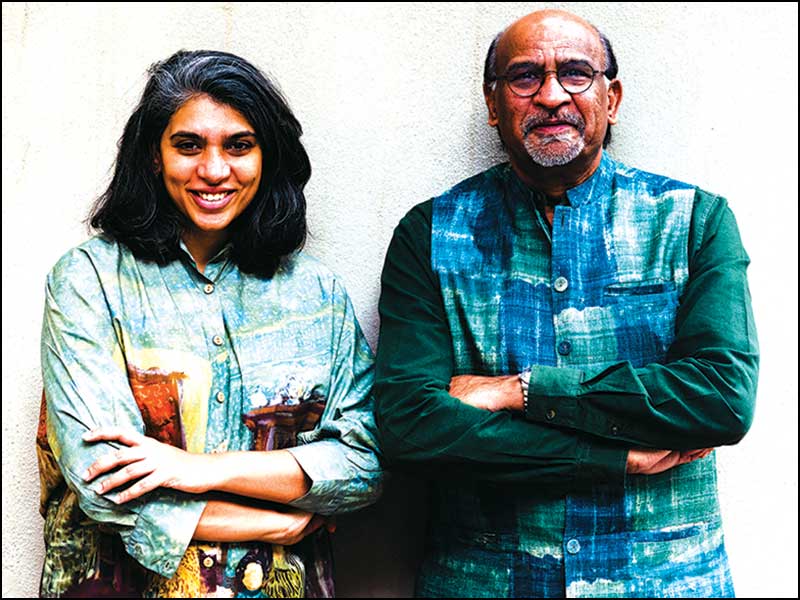

Green has basically no generic definition. It is a very contextual subject. To impart green character to a building doesn’t only have to comply with certifications. We’ve surmised that by ticking certain components on a certificate or by keeping up with building norms, we can make our buildings green. It is not a prototype model one can irrelevantly apply anywhere in the world. It is about understanding the context, where your building sits, the nature around it, the macro-micro climate and everything that restores the natural balance.

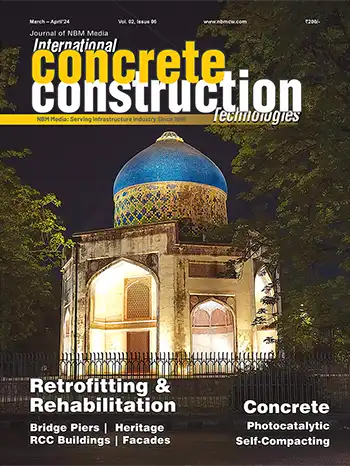

Head office Delhi Pollution Control Committee, New Delhi

Head office Delhi Pollution Control Committee, New DelhiToday, going green is synonymous with drawing heavily from alien techniques, with exorbitant financial concerns. A design lacking in cost efficiency can never be green, plus, there are financial and human resources that are rarely acknowledged. Each of the three has to balance the other in order to create self-sufficient sustainable buildings. Any irregularity between the three, be finances or engaging high manpower that adds to the carbon footprint, end up disturbing the macro climate. Sustainability, after all, is about achieving the balance.

We need to revert to our roots in order to generate sustainable and eco-friendly structures rather than just striving for green certifications from the West.

I admire...

From the vernacular houses of Kerala to the Havelis and step wells of Rajasthan and Gujarat, one comes across absolutely balanced structures rooted in the regional landscape. Where there is any imbalance created by nature, vernacular architecture has always responded positively in filling the void. Step wells were built in barren lands to conserve water and create an enclosed ambient micro climate for travellers to drink and rest. By taking care of the human resource, this architecture took care of the natural balance. Panna Meena Baoli and Sagar Lake in Amer, Rajasthan, built around the 16th century, are interconnected reservoirs that conserve rainwater. Percolating and getting filtered through layers of fine silt and eventually to an impermeable layer of clay, the water flows through the lake and gets collected in wells.